Chuck Turner is going to jail, but it's the Feds who should be hanging their heads in shame

Power play

By KYLE SMEALLIE AND HARVEY SILVERGLATE | March 23, 2011

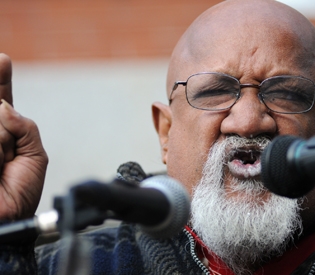

Chuck Turner reports to prison Friday. If his sentence sticks, that's where the 70-year-old former Boston city councilor will spend the next three years.

Turner was convicted of attempted extortion, for accepting a bribe from a paid FBI informant, and also of giving false statements to federal officials, for lying about it to investigators. But there is much more to the case. Stepping back, it becomes clear that Turner was targeted by the FBI because he refused to play ball and build the government's case against another Massachusetts politician, former state senator Dianne Wilkerson. This is all about federal power — the power to destroy any who won't cooperate with the government's agenda.

At the beginning, this investigation was about the lucrative business of alcohol; in particular, how the city of Boston doles out coveted liquor licenses. By all indications, Wilkerson was on the take. She accepted multiple cash hand-offs (totaling $23,500) and appeared to initiate legislative action in return.

But in this mess, where does Turner fit?

US Attorney Carmen M. Ortiz asserted that investigators "began with Wilkerson and followed the trail to Turner," the Boston Globe reported. But this was a trail blazed by the FBI itself. The connection, FBI agents testified, was a June 2007 e-mail Wilkerson sent to multiple city councilors, including Turner, concerning liquor-license distribution. Without explicitly stating so, her e-mail suggests that the licensing board improperly delayed approval of certain African-American applicants.

The next day, Turner responded to Wilkerson and several other city councilors: "I will send you a proposed hearing order to see if it appropriately frames the issues." Turner wanted to hold a hearing. This is what Turner did all the time. Yet this was evidence enough for the FBI to pay an informant some $29,000 and send him to Turner's Roxbury office to "feel him out."

Of course, the now-infamous video, taken August 3, 2007, in Turner's district office, doesn't lie. Turner took something, and it appears to be cash. The feds say it was $1000; Turner testified that he had no idea of the amount. It's important to note, however, that in a departure from standard procedure, the FBI agents did not search the informant, Ronald Wilburn, after the exchange to be certain that he handed all of the cash to Turner.

The amount given to Turner becomes important because local campaign-finance regulations allow candidates to accept cash contributions up to $50, provided it is duly recorded and reported. If the cash given to Turner was $50 or less, his only violation would have been only a minor fundraising-reporting omission.

GAINING LEVERAGE

Turner's counterattack — that he and Wilkerson were targeted because they are black — was unproductive and unverifiable, an allegation that Ortiz quieted easily. Far more difficult to refute is the more likely motivation: the federal government wanted to gain leverage on Turner, so they could pressure him into cooperating with their plans.

Consider, for instance, the absurd notion that Turner was extorting Wilburn. This may seem like hair-splitting legalese, but it speaks to why the case should never have been brought in the first place. Under existing law, bribery of state officials — payments initiated by the citizen — is not a distinct federal crime. Extortion, however, is. But extortion requires some kind of threat — the public official demanding, for example, payment to refrain from harming the citizen's interests. By all indications, Wilburn didn't fear retaliation if he didn't pay up.

At any rate, Turner would not have made an effective extortionist. His hallmark was holding hearings, not necessarily getting results. There is a role for such officials in public life, of course. As Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis once said, sunlight is the best disinfectant, and Turner specialized in casting sunlight.

Prosecutors, oddly, conceded that Turner had little to sell. "There is substantial doubt," they asserted in a memorandum requesting a heavy prison sentence, "about Turner's effectiveness as a public servant." A strange assertion, for if he could not get approvals from the licensing board, why would any businessman succumb to his supposed extortion demands? This is more than a mere detail, for it weighs heavily toward a conclusion that Turner saw the Wilburn payment as an ordinary campaign contribution, rather than a payoff.

One might think that the news media would pick up on this. But from the moment the feds leaked the grainy photos of the handoff, the reporting angle (with a few exceptions, such as WBUR's David Boeri) was all but set: the press saw red meat. Reporters perhaps lost sight of the fact that, in their role as watchdog over government conduct, the actions of the feds deserved as much, if not more, scrutiny than the likely very minor improprieties of a city pol. If voters don't like Turner, or if they smell a whiff of dishonesty, they can express their displeasure at the ballot box. But if those same citizens dislike what federal prosecutors and FBI agents are doing in the people's name and on their dime, they have little practical recourse.

Which makes all the more revolting the fact that prosecutors, in their memorandum requesting 33 to 41 months in prison for Turner, used the politician's own overheated statements against him — in essence asking the court to punish him for his free speech. By asserting that the investigation was racially motivated, Turner's words "have been corrosive to respect for important public institutions and the rule of law," prosecutors argued to Judge Douglas Woodlock.

THROWING BOULDERS

Coming from the Massachusetts US Attorney's Office, in connection with a case launched by the Boston FBI office, the feds's air of piety was nothing short of stomach-churning. Just last month, a federal appeals court saw fit to deny compensation to the family of an innocent man gunned down as a result of the Boston FBI's office working with the mobster Whitey Bulger. And federal prosecutor Jeffrey Auerhahn, found by another judge to have hidden evidence that could have shown that a man convicted of murder was innocent, continues to serve in the US Attorney's Office.

Even if prosecutors were throwing boulders from their glass house, the onus was ultimately on Woodlock to see through this ruse. In this regard, he utterly failed, seeing fit to hand down a shockingly harsh three-year sentence — only a few months shorter than that of Wilkerson, a repeat offender. Woodlock took specific issue with Turner's testimony, finding it implausible that the 70-year-old couldn't remember meeting the FBI's informant.

But Woodlock, a former corruption prosecutor turned judge, perhaps unsurprisingly didn't see the bigger picture. He didn't see the possibility — indeed, the likelihood — that the feds led Turner into a scenario that appeared far more pernicious than the reality. He didn't see that a local politician was targeted by federal prosecutors for not helping them build their case against Wilkerson.

In the quest for Turner's scalp, neither federal law-enforcement authorities, nor the supposedly independent federal judiciary and news media, properly played the roles assigned to them in our constitutional system — which continues to suffer mightily under the weight of stings and set-ups that too often mask, rather than reveal, the truth.

Kyle Smeallie can be reached at kyle@harveysilverglate.com. Harvey Silverglate can be reached at harvey@harveysilverglate.com.